The sensation remains with him: the pain of the pliers biting into his skin, and the smell of his own flesh burning.

It is Egypt, 1991.

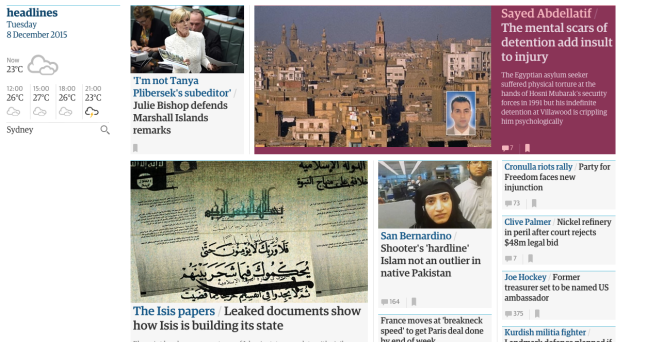

Sayed Abdellatif is in a building, somewhere – he does not know where – in Cairo, in the custody of the feared state security investigations service (SSIS), the principal security and intelligence agency of the dictator Hosni Mubarak’s regime.

A few hours earlier, the devout 19-year-old had been praying in a mosque when it was raided by members of the SSIS. Everyone inside was arrested, even the children.

Now, sitting in a cell with 15 or 20 other men, Abdellatif does not know why was he was arrested, with what – if anything – he will be charged, or when he might be released.

At regular intervals guards walk into the cell. They blindfold a prisoner, and lead him away.

Finally it is Abdellatif’s turn. Bound, and in the arms of guards, he is taken away to be tortured.

In an interview years later with Australian immigration authorities, Abdellatif is able to recall the methods of torture with chilling detail: “They would tie your hands behind your head and dangle you from a bar. They would use lit cigarettes against your body to put the cigarette out against your skin.”

Through the blindfold he could feel heated metal tools being used to burn his hands.

“This part of my thumb [there] was like a plier where they heat it up and pinch the skin, and they put cigarettes [sic] out on my legs.”

Each interrogation runs for several hours. The time between is spent in the holding cell waiting, wondering when your time will come again.

Most of the interrogations happen at night, Abdellatif says.

“They would put you in a room and fill it with water, about a foot of water, and so you couldn’t sleep, and leave you there, and put live electricity into the water.”

Hours become days become weeks. After two months, without warning, Abdellatif is released back on to the streets of Cairo.

But his arrest is only the beginning.

His life is about to descend into a haze of repeated arrests, detention, torture and ultimately exile.

Twice more, Sayed is arrested by the same security forces. He is held for three months each time.

In 1992, he flees Egypt.

TWENTY-THREE years later, Sayed Abdellatif sits in the noisy visitors hall of the high-security wing of Sydney’s Villawood detention centre.

Seated at a table near the middle of the room, he says a quiet “Hello” to a few fellow detainees who walk past.

But many he doesn’t know. They are just passing through, he says, here for a few weeks before they are moved somewhere else. He is here forever, he fears.

Abdellatif faces indefinite detention despite being found to have a prima facie claim to refugee status – he is a person Australia is obliged to protect – and an assessment from the inspector-general of intelligence and security that made clear he poses no threat to Australia’s national security.

Having fled Egypt in 1992, Abdellatif lived in exile across the world, at the fringes of the societies where he sought safety and security. He moved from Albania to the UK, Iran, and through Indonesia and Malaysia before finally reaching Australia in May 2012. Along the way he married and had six children: four daughters, followed by two sons.

The Abdellatifs’ claim for protection began unremarkably enough. After a series of interviews and corroborations of his evidence, Australian authorities found Abdellatif and his family to have a prima facie claim to refugee status: that is, they have a well-founded fear of persecution in their homeland.

But when authorities also uncovered a historical – and flawed – Egyptian conviction against Abdellatif, his case is suddenly transformed into a political lightning rod for national security, with the Abbott-led Coalition, then in opposition, using the case to lambast the Gillard government’s handling of border security.

Labelling Abdellatif a “pool fence terrorist”, Abbott accused the government of failing to notice that a “convicted jihadist terrorist was kept for almost 12 months behind a pool fence”.

In 1999, seven years after he left Egypt, Abdellatif had been convicted in absentia in a mass show trial of 107 men in Cairo, a trial that was condemned as unfair by Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, and has since been discredited in his home country as a politically motivated suppression of Islamic opposition.

A Guardian Australia investigation into the trial uncovered further serious irregularities, finding that the three most serious convictions on the Interpol notice were entirely false, and that the crimes had never even been alleged against Abdellatif in his trial.

That investigation resulted in Interpol dropping all convictions for violence against him.

Further court documents later uncovered by Guardian Australia – and which have been provided to Australian authorities – showed that the admissions used to convict Abdellatif on other charges, of membership of an extremist group and using forged documents, were obtained under torture. Abdellatif has denied these charges.

In 2014 Australian immigration department officers recommended to the then immigration minister, Scott Morrison, that Abdellatif and his family should be granted visas and released into the community. That was rejected by the minister.

In June this year the United Nations human rights council found Abdellatif’s detention was “illegal”, “arbitrary” and “indefinite”, and directed Australia to release the family and provide compensation for their wrongful detention.

The current immigration minister, Peter Dutton, has allowed Abdellatif to apply for a temporary protection visa, but his application has been stalled for more than five months, without any progress towards ending the family’s continued detention and separation.

Now, further documents obtained by Guardian Australia show the department has been told consistently over three years that Abdellatif’s mental health, and that of his family, is being harmed by his continued and indefinite high-security detention.

In confidential reports and his immigration entry interview, Abdellatif detailed to Australian authorities the full extent of his experience under Mubarak’s dictatorship.

He told immigration officials he does not know why he was targeted.

“I was 19 years old, a time when your [sic] thinking about your future. The only crime I committed was being in the mosque at that time.”

Mubarak’s military regime was ousted after three decades during Egypt’s 2011 revolution. His secular regime was widely condemned by human rights groups for brutal crackdowns on anyone seen to be part of the country’s Islamic opposition.

“Under the martial laws, the state security would come and arrest a group of people to show they were doing their job,” Abdellatif said.

“It starts as a random thing, then they start a file for you and then arrests will be regular.”

The inspector-general’s report found Abdellatif did not attempt to conceal or lie about his identity or past to Australian authorities at any time.

While in detention in Australia, Abdellatif was examined by a psychologist from the Service for the Treatment and Rehabilitation of Torture and Trauma Survivors (STARTTS).

A psychologist’s report from his detention in the UK also found the marks on Abdellatif’s body were consistent with a victim of torture.

It’s like a dark cloud. It’s frightening. Something grips my heart, it’s difficult to breathe

“He has one scar on his body that is typical of a cigarette burn, and others that are consistent with his story,” the psychologist said.

But his history of torture has left Abdellatif with not only physical scars, but psychological ones: injury compounded by his continuing detention.

“Symptoms have been further exacerbated by the fact that Mr Abdellatif remains in an environment he perceives as punitive and unsafe without a foreseeable resolution,” the STARTTS report told immigration department authorities in its assessment of Abdellatif’s psychological condition.

In detention, Abdellatif suffers nightmares, flashbacks, headaches, panic attacks and uncontrollable shaking. He has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression.

“It’s like a dark cloud. It’s frightening. Something grips my heart, it’s difficult to breathe,” he told one psychologist.

In detention, Abdellatif feels powerless and unable to protect those who are closest to him, an anxiety most acute around his youngest son. The five-year-old has spent his entire life in detention.

“Mr Abdellatif feels that he is not able to completely fulfil his role and responsibilities as a father of his family while he lives away from them, and that he is not able to offer his protection,” the STARTTS report says.

Separation from his family compounds his sense of loneliness and isolation.

“Mr Abdellatif’s experiences have significantly been exacerbated as a result of the extended duration of his detention and the separation from his family.”

The report finds Abdellatif’s health is being harmed by his detention.

“He would benefit from being released into the community with his family, in order to prevent further deterioration of his health.

“Providing a resolution to Mr Abellatif’s immigration status and ending his indefinite detention appears to be a vital precondition to his recovery.”

Internal departmental emails indicate the Abdellatif children are also affected by their father’s – and their own – detention.

A psychologist’s email reported to department staff that one Abdellatif son was “withdrawn” and “highly anxious about his father’s welfare” after Abdellatif was removed to higher-security detention.

The psychologist recommended: “In order to prevent further deteriorating of [his] mental state, his father[should] be united with his family.”

In May Abdellatif and his family were offered hope with the possibility of a temporary protection visa. “It was like light coming into a dark world”, he told Guardian Australia during one visit at Villawood.

But his hope is tinged with the uncertainty and despair of a limitless detention, a waiting game that could be ended in weeks, but may take months or years.

“I feel like I’ve become a file and this file has been thrown away,” he told a psychologist in detention.

“They say, ‘We know you’re innocent,’ but we still keep you in detention.”